Metallocene Polyethylene Films as Alternatives to Flexible PVC for Medical Device Fabrication

The volume of plastics used to produce disposable medical devices and supplies is projected to grow to more than 1.6 billion pounds by the year 2000.1 Efforts aimed at conserving resources and containing costs have encouraged device manufacturers to seek alternative materials that can meet device performance requirements while using less material. Fabricators will look for opportunities to reduce the thickness, weight, or volume of device components without compromising the structural integrity or functionality of the device. For disposable devices and supplies, a reduction in raw materials will result in a direct reduction of waste.

Flexible polyvinyl chloride is one of the largest-volume film materials used in the manufacture of medical devices, and thus presents a significant opportunity for both raw material and waste reduction. Because PVC film provides a wide array of

functional performance characteristics at a low cost, alternative materials will need to offer similar performance at comparable cost. Performance properties of PVC important to the medical device industry include its long, successful track record in

medical applications; a breadth of properties achievable by compounding; the ability to be fabricated by RF welding and solvent bonding; the ability to be sterilized by autoclave, ethylene oxide (EtO), or gamma (although some yellowing can occur with 2,3gamma); a wide service temperature; durability and chemical resistance; and good breathability, elasticity, and clarity.Recent developments in metallocene single-site catalyst technology make possible precise control of molecular architecture and enable the production of polyolefin resins with very low densities and narrow molecular-weight distributions. Metallocene-catalyzed polyethylene copolymer resins (mPE) are currently being made with specific gravities in the range of 0.86–0.92 and comonomer content of 0–45%. Polyolefin plastomer resins formulated as ethylene-octene copolymers with less than 20% comonomer (produced by Dow Chemical Co., Midland, MI) have demonstrated enhanced toughness, sealability, clarity, and elasticity.

The toughness of mPE resins can allow for thinner, lighter-weight films, and the lower density of the mPE films results in a higher yield than is possible with PVC, producing more film area per pound. Very stable following sterilization by either radiation or EtO, mPE films provide good low-temperature flexibility and impact resistance, and have a low seal-initiation temperature.

The lower melt temperatures of the mPE resins (less than 110°C) make these films inappropriate for products requiring 4

autoclave or high-temperature steam sterilization.This study was designed to test the suitability of films made using mPE resins as alternatives to flexible PVC films for medical device and appliance applications. Films used in this study were fabricated from ethylene-octene copolymer mPE resins with specific gravities between 0.88–0.90 and comonomer content of 12–20%.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDUR>

|

Table I. Film samples evaluated. | |||

|

Abbreviation |

Description |

Film Thickness (mm) |

Film Density (g/cm3) |

|

mPE film 1a |

MDF 7200 monolayer, embossed cast mPE film |

0.15 and 0.25 |

0.905 |

|

mPE film 2a |

XUR-52 monolayer, embossed cast mPE film |

0.15 and 0.25 |

0.895 |

|

PVC film 1b |

E30-194 medical-grade PVC film |

0.18, 0.20, 0.23 |

1.25 |

|

PVC film 2b |

E30-2152R medical-grade PVC film |

0.25 |

1.26 |

|

a Dow Chemical Co., Midland, MI. | |||

study. They included two mPE films with different densities and two medical-grade PVC films

that were designated by the manufacturer for use in medical collection or drainage bags. The mPE films used were 0.25 and 0.15 mm (10 and 6 mil) thick, and the PVC films were 0.18, 0.20, 0.23, and 0.25 mm (7, 8, 9, and 10 mil) thick. Since the films were embossed on one surface, thickness was reported as a nominal thickness per ASTM E 252.5

Standard physical properties evaluated for all films included tensile strength, elongation, modulus, tear resistance, puncture resistance, and barrier characteristics. The films were conditioned according to ASTM D 882 and then tested following the ASTM method, as shown in Tables IV.

|

Table II. Physical properties of mPE films. | ||||||||||||

|

|

Test Units |

|

mPE Film 1 |

mPE Film 1 |

mPE Film 2 |

mPE Film 2 | ||||||

|

Physical Property |

Test |

SI |

English |

Test |

SI |

English |

SI |

English |

SI |

English |

SI |

English |

|

Film thickness Film density Film nominal yield |

ASTM E 252 ASTM D 4321 |

mm |

mil |

- |

0.15 |

(6) |

0.25 |

10 |

0.15 |

6 |

0.25 |

10 |

|

Yield tensile strength |

ASTM D 882 |

MPa |

psi |

MD |

5.0 |

730 |

4.8 |

690 |

4.0 |

580 |

4.0 |

580 |

|

Ultimate tensile strength |

ASTM D 882 |

MPa |

psi |

MD |

31.8 |

4610 |

28.1 |

4080 |

30.6 |

4440 |

25.4 |

3690 |

|

Ultimate elongation |

ASTM D 882 |

% |

% |

MD |

700 |

700 |

730 |

730 |

625 |

625 |

670 |

670 |

|

Toughness (energy to break) |

ASTM D 882 |

J/m3 |

in-lb/cu in. |

MD |

86.2 |

12500 |

83.4 |

12100 |

65.5 |

9500 |

63.7 |

9240 |

|

1% secant modulus |

ASTM D 882 |

MPa |

psi |

MD |

62.8 |

9100 |

61.4 |

8900 |

43.4 |

6290 |

44.2 |

6410 |

|

Elmendorf tear |

ASTM D 1922 |

gms |

gms |

MD |

1680 |

1680 |

3410 |

3410 |

810 |

810 |

1780 |

1780 |

|

Elmendorf tear |

ASTM D 1922 |

g/mm |

g/mil |

MD |

11000 |

280 |

13400 |

341 |

5310 |

135 |

7010 |

178 |

|

Puncture resistance |

ASTM D 3763 |

J/m3 |

in-lb/cu in. |

- |

9.2 |

1330 |

11.4 |

1650 |

14.3 |

2070 |

17.9 |

2600 |

|

Oxygen transmission rate Water vapor transmission rate |

ASTM D 3985 ASTM E 96 |

cm3/m2 |

cm3/100 sq in. |

- |

2635 |

170 |

1550 |

100 |

3490 |

225 |

1920 |

124 |

|

Table III. Physical properties of PVC films. | ||||||||||||

|

|

Test Units |

|

PVC Film 1 |

PVC Film 1 |

PVC Film 1 |

PVC Film 2 | ||||||

|

Physical |

Test |

SI |

English |

Test |

SI |

English |

SI |

English |

SI |

English |

SI |

English |

|

Film thickness |

ASTM E 252 |

mm |

mil |

- |

0.18 |

7 |

0.20 |

8 |

0.23 |

9 |

0.25 |

10 |

|

Yield tensile strength |

ASTM D 882 |

MPa |

psi |

MD |

8.8 |

1270 |

6.7 |

970 |

7.2 |

1050 |

6.0 |

870 |

|

Ultimate tensile |

ASTM D 882 |

MPa |

psi |

MD |

19.9 |

2890 |

25.0 |

3630 |

23.7 |

3430 |

23.7 |

3430 |

|

Ultimate elongation |

ASTM D 882 |

% |

% |

MD |

185 |

185 |

285 |

285 |

270 |

270 |

270 |

270 |

|

Toughness |

ASTM D 882 |

J/m3 |

in-lb/cu in. |

MD |

27.8 |

4030 |

46.9 |

6805 |

43.7 |

6340 |

41.9 |

6080 |

|

1% secant modulus |

ASTM D 882 |

MPa |

psi |

MD |

51.8 |

7510 |

38.7 |

5610 |

40.6 |

5880 |

34.4 |

4990 |

|

Elmendorf tear |

ASTM D 1922 |

gms |

gms |

MD |

2140 |

2140 |

1490 |

1490 |

1220 |

1220 |

1070 |

1070 |

|

Elmendorf tear |

ASTM D 1922 |

g/mm |

g/mil |

MD |

12000 |

306 |

7320 |

186 |

5350 |

136 |

4210 |

107 |

|

Puncture resistance |

ASTM D 3763 |

J/m3 |

in-lb/cu in. |

- |

7.17 |

1040 |

8.6 |

1250 |

7.6 |

1100 |

7.0 |

1020 |

|

Oxygen transmission |

ASTM D 3985 |

cm3/m2 |

cm3/100 sq in. |

- |

620 |

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table IV. Film performance properties. (*Denotes that sample did not fail at maximum test load/height.) | |||||||||||

|

|

mPE Films |

PVC Films | |||||||||

|

Performance Property |

Test Method |

Test Parameter |

Unit |

mPE 1-6 |

mPE 1-10 |

mPE 2-6<,/SPAN> |

mPE 2-10 |

PVC 1-7 |

PVC 1-8 |

PVC 1-9 |

PVC 2-10 |

|

Film thickness |

, ASTM E252 |

- |

mm |

0.15 |

0.25 |

0.15 |

0.25 |

0.18 |

0.20 |

0.23 |

0.25 |

|

Airburst test |

- |

Time to burst |

sec |

170 |

184 |

288 |

269 |

104 |

72 |

105 |

73 |

|

Resistance to bursting |

BS 7126- |

Load applied to failure |

N |

1410 |

>2300* |

>2300* |

>2300* |

>2300* |

>2300* |

>2300* |

>2300* |

|

Resistance to impact |

BS 7126- |

Drop height to failure |

m |

>7.6* |

>7.6* |

>7.6* |

>7.6* |

2.7 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

3.1 |

The puncture-resistance test conducted on the film material is similar to ASTM D 3763, but is run at a lower impact speed. One sheet of film is held in a clamp that has a circular opening 45 mm (1.8 in.) in diameter. A 12.7-mm-diam (0.5-in.) spherical probe attached to a load cell on a moving cross-member is pushed through the film at a speed of 500 mm/min (20 in./min), and the resulting total energy per unit area required to puncture the film is recorded.

For the purposes of this study, liquid-collection bags were chosen as a typical medical device application. The bags are commonly made from two sheets of film welded together around the perimeter, with an inlet port sealed into one end; they may also include an outlet port and a means of measuring the volume of the liquid contents. For this study, bags were made using two rectangular plies of film totaling 432 cm2 (0.5 sq ft) each.

The collection bags were made using radio-frequency (RF) welding to bond the perimeter. PVC films and other polymers with high dielectric loss factors respond to RF energy and are commonly fashioned with RF welding equipment; however, mPE films and other low-loss polymers do not respond well to conventional RF welding. Successful RF welding of mPE films requires the addition of a mechanical "catalyst" to the existing RF equipment. The mPE bags for this study were produced using RF welding equipment (stabilized at 27.12 MHz) that had been modified with a reusable catalyst film by Plastics Welding Technology (Indianapolis). Hot-bar or impulse heat-seal equipment can also be used to form mPE films into devices.

The British Standards Institution (BSI) has developed a performance standard for liquid collection bags (BS 7126 and ISO 8669) that includes test methods for determining resistance to bursting (part 101, appendix G) and resistance to impact damage (part 101, appendix H).6 The method for determining resistance to bursting involves filling a bag with its rated volume of water (or 90% of its reference volume), sealing any openings, and placing the bag horizontally under a flat rigid plate on which weight is added to impose a 350-N (78.7-lb) force on the filled bag. After the load is applied for 1 minute, the bag is examined for leakage or bursting. The method for determining resistance to impact damage involves filling the bag to 50% of its reference volume and sealing it without entrapping air in it. The bag is then dropped from a height of 500 mm (19.7 in.)—so that the bottom hits a hard surface—and examined for leakage or bursting. The reference volume for the bags used in this study was 1240 ml; they were filled with 1116 ml of water for the bursting test and with 620 ml of water for the impact test.

The burst strength of the finished bags was tested by filling them with air at a controlled pressure and flow rate and measuring the time required to fill each bag to the point of failure. Bags fabricated with two 432-cm2 plies of film were inflated with air at a rate of 5.36 L/min and a line pressure of 0.083 MPa (12 psi) until they burst.

RESULTS

The results of the physical property tests are shown in Table II for the mPE films and in Table III for the PVC films. For the physical properties tested, the mPE films demonstrated similar or superior results when compared with the PVC film of the same thickness. Significant differences—when the mPE films showed property improvements of greater than 50% over the PVC film—were seen in results of the elongation, toughness, tear-strength, and puncture-resistance tests.

The mPE films also showed physical property advantages when compared with thicker PVC films. The properties of the 0.15-mm-thick mPE films (of two different densities—Types 1 and 2—as shown in Table I) were comparable or superior to those of PVC films of all tested thicknesses—including the 0.25-mm-thick film—demonstrating significant improvements in tensile strength, elongation, toughness, and puncture resistance.

The water vapor and oxygen transmission rates of mPE films are inversely related to their density and thickness: as the density or thickness increases, the transmission rates decrease. The barrier properties of PVC films are a function of the formulation and plasticizer content: in general, the more highly plasticized films have higher transmission rates. The mPE films tested had about five times lower water vapor transmission rates and about four times higher oxygen transmission rates than the PVC films. Normalized for thickness, the water-vapor transmission rates (gm?mm/m2/24 hr at 37°C and 90% RH) of Types 1 and 2 mPE film were 0.93 and 1.26, respectively, compared with 6.0 for Type 1 PVC film. The oxygen transmission rates (cm2?mm/m2/24 hr at 23°C and 1 atm) for the Types 1 and 2 mPE film were 390 and 500, respectively, compared with 110 for Type 1 PVC film.

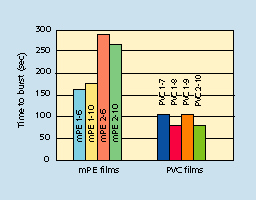

The performance property tests conducted using the water-filled bags demonstrated significant differences between the mPE films and PVC film. Results are shown in Table IV and Figures 1 and 2. The resistance-to-airburst test results shown in Figure 1 again demonstrated that the mPE films can elongate more than the PVC films before failing, as previously shown by results of the physical property tests. The PVC bags burst along the weld edge after air pressure was applied for 72–105 seconds. The bags made with Type 1 mPE failed after 170–184 seconds, and those with Type 2 mPE film failed after 269–288 seconds—in each case because the body of the bag had been stretched beyond the yield point. The results for all films were not shown to be directly related to film thickness.

Figure 1. Resistance to airburst of a 432-cm2 bag filled with 12 psi air at 5.4 L/min.

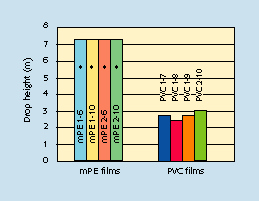

Figure 2. Resistance to impact of a 432-cm2 bag with 620 ml water dropped on concrete. (*Denotes that film did not fail.)

The BSI standard for resistance to impact damage of a water-filled bag requires that it not leak or fail after being dropped from a height of 0.5 m (1.6 ft). None of the tested mPE or PVC films failed the 0.5-m drop, so the drop height was increased to determine the failure point. The PVC films failed along the weld edge at a drop height of 2.5–3.1 m (failure was not related to thickness), while none of the tested mPE films failed at the maximum drop height of 7.6 m (25 ft).

The BSI standard for resistance to bursting of a water-filled bag specifies that it must withstand a 350-N (78.7-lb) load without leaking or failing. None of the tested mPE or PVC films failed at a 350-N load, so the load was increased to determine a failure point. The maximum load that could be applied with the test apparatus was 2300 N (516 lb). Within this upper load limit, only one of the tested films failed: the mPE 1-6 film (0.15-mm thick), which failed at a load of 1410 N (316 lb). All of the other films—mPE and PVC—withstood the 2300-N load.

CONCLUSION

The films made with metallocene polyethylene resins that were used in this study showed superior physical and performance properties in several areas as compared with flexible PVC films. These included tensile strength, elongation, and toughness; resistance to puncture, impact, and bursting; and water-vapor barrier characteristics.

The study also demonstrated that mPE films can provide physical properties comparable to significantly thicker PVC films. For example, a 0.15-mm-thick mPE film can provide better toughness and puncture, impact, and burst resistance than a 0.25-mm-thick PVC film. This can enable product designers to specify a much thinner film—reducing thickness by 25% or more compared with PVC—without compromising performance.

The combination of a film density approximately 30% lower than that of PVC and improved properties results in a thinner, lighter-weight product that meets performance needs while reducing the volume of material required—making the product lighter to ship and use and creating a lower volume of waste material for disposable devices. The higher yield can also allow mPE films to be very cost-competitive: although PVC resins cost less per pound than mPE resins, the price per unit area of film or per finished device can be comparable.

In addition to the physical properties noted, mPE films offer a number of performance attributes that make them well suited for use in many medical devices. Among these properties are excellent flexibility over a wide temperature range, good cold crack and pinhole resistance, toughness and impact resistance at low temperatures, and the ability to be sterilized either by EtO or by gamma irradiation (with no discoloration)

Fabrication of devices with mPE films can be accomplished using many types of operations, including heat and impulse sealing, adhesive bonding and lamination, thermoforming, and printing. The mPE films can also be welded using conventional RF welding equipment modified with a catalyst film, with strong welds and tear seals achievable by this method. Solvent bonding—a technique commonly used for joining PVC components—does not work well with mPE films.

For manufacturers of a wide range of medical devices—from collection bags to drainage systems to inflatable devices—mPE films can provide a high-performance, practical, and cost-effective alternative to PVC films.

REFERENCES

1. Disposable Medical Supplies, Cleveland, The Fredonia Group, 1996.

. Shang S, and Woo L, "Selecting Materials for Medical Products: From PVC to Metallocene Polyolefins," Med Dev Diag Indust, 18(10):132–146, 1996

3. Hong KZ, "Poly(vinyl chloride) in Medical and Packaging Applications," in Society of Plastics Engineers, Inc., Technical Papers, vol XLI (ANTEC 95), Brookfield, CT, Society of Plastics Engineers, pp 4192–4198, 1995.

4. Moldovan D, "POPs and POEs—Resins for the 21st Century," in Proceedings from the Medical Design and Manufacturing Orlando Regional Show Series (supplement), Santa Monica, CA, Canon Communications, 1995.

5. Storer R (ed), Annual Book of ASTM Standards, West Conshohocken, PA, ASTM, 1993.

6. Wood L, and Keynes M, "BS 7126 Urine Collection Bags," London, British Standards Institution, 1989.Link:http://service.labthink.cn/en/article-literature-info-11011895.html

Labthink Copyrights. Please do not copy without permission! Please indicate source when copy.

Member Registration and Login In

| If you are already a member of us, please login in! | If you are not a member of us, please register for free! | ||

·Forget password? |

|

·Terms and Conditions If you have questions, please phone 86-531-85811021 |

|